What the Ferguson Commission Gets Right and Wrong About Public Transportation in Saint Louis

The Ferguson Commission recently released a report that outlined a series of problems and proposed solutions to racial disparities in the Saint Louis region. One of the areas that the commission looked at was transportation, specifically public transportation.

The commission rightfully pointed out that for those who do not have access to a personal vehicle, the Saint Louis region can be difficult to navigate. Few jobs are easy to get to via a short transit trips, and car ownership can be costly. The commission’s recommendations, channeling Samuel Gompers, can mostly be described as “more.” The group specifically recommended a North-South MetroLink expansion.

Unfortunately, the commission’s report does not get at the reasons why public transportation is of so little use in Saint Louis, reasons that will make a billion-dollar plus MetroLink expansion more window dressing than beneficial reform.

To start, it is important to understand that fast and effective transit relies on high workplace and population density. But in Saint Louis, employment and population are spread out across a wide geographic area, much of which the existing transit system (Metro) does not serve. The majority of residents do not live or work in the city’s urban core and most commutes are suburb-to-suburb. While this situation describes many American cities, in Saint Louis the problem is particularly acute. Saint Louis’s may rank 17th nationally in terms of total metro population, but it is only 31st largest when we look at population within 10 miles of city hall. Despite the population dispersal, Saint Louis’s public transportation system is geared towards moving people into and around the city core, not between suburbs. It should come as no surprise that most people, even the economically disadvantaged, do not find the system useful.

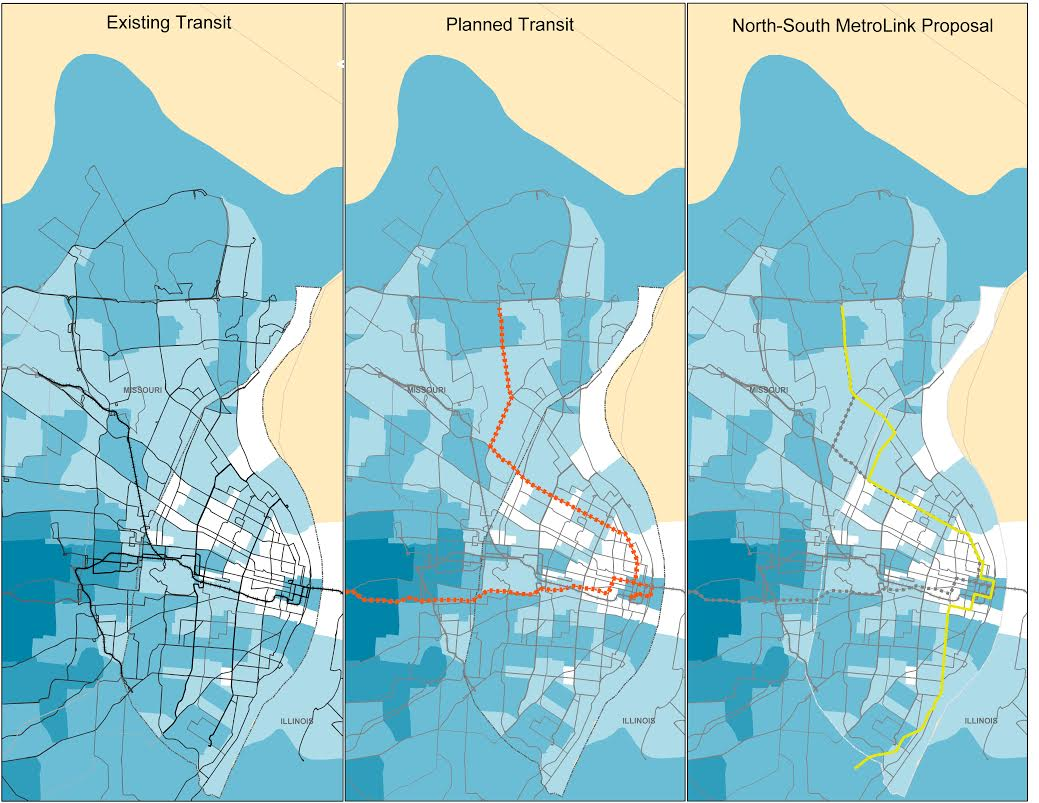

What effect will a MetroLink expansion have on this situation? Saint Louis already has an extensive (and expensive) public transportation system. That system is most readily available in the areas the proposed MetroLink expansion would serve, as the map below shows:

If the goal is providing new access to employment centers outside of the city center, the plan has little value. The line would of course speed up travel for some (and convince some who don’t use transit to ride more often), but that will mean only marginally lower commute times for transit users who do not live and work near the MetroLink.

While its impact on employment access will be low, the cost of a MetroLink expansion will be high, likely more than a billion dollars. Worse yet, if history is any guide, the expansion will be funded with general sales taxes, which are known to be regressive. If regional mobility and opening up more of the region to the poor is what the commission cares about, more bus routes with better service and more destinations are orders of magnitude less expensive to create. Rail enthusiasts often accept this cost disparity because rail lines are part of a grand urban rebirth vision, with immediate mobility gains taking lower priority (or ignored altogether). That the commission did not attempt to search for new transit solutions more germane to the problems at hand is disappointing.